So marvelous to see Kamala Harris make history last night, and to hear her invoke so many of the remarkable women whose achievements have empowered and inspired her. History matters.

In that spirit, and in honor of the teachers who started a most challenging school year this week, I offer this excerpt from Chapter 1 of Color and Character, which sets the stage for the accomplishments of West Charlotte’s staff and students during Jim Crow segregation.

The dictates of white supremacy meant that West Charlotte opened with far fewer resources than Charlotte’s white high schools. The school had been built without a lunchroom, auditorium or gymnasium. It had a handful of social studies maps, a few biology supplies, and some library books, but no radio, no projector, and no lab equipment for chemistry, physics, general science or home economics. The situation was no longer quite as bad as it had been in the 1910s, when North Carolina spent nearly twice as much on white students as on black students, or in the 1920s, when the state spent ten times as much on white school buildings as on black, but the difference remained significant.

What West Charlotte did have was teachers. The growth of high school and college opportunities in the 1920s had expanded North Carolina’s pool of young, well-educated African Americans, and teaching was one of the few professions to which they could aspire. Longtime English teacher Elizabeth Randolph, a Shaw University graduate who came to West Charlotte in 1944, had wanted to be a teacher since she was a little girl. But, she explained, she also had little choice. “I can’t think of anything else I could have done,” she noted. “If you didn’t get a job teaching, you went to the post office or you did something that was menial.” As principal of an urban high school, Clinton Blake could lure prospective teachers with the amenities of city life, as well as a city-funded supplement to the state salary. He had no shortage of talented individuals to choose from.

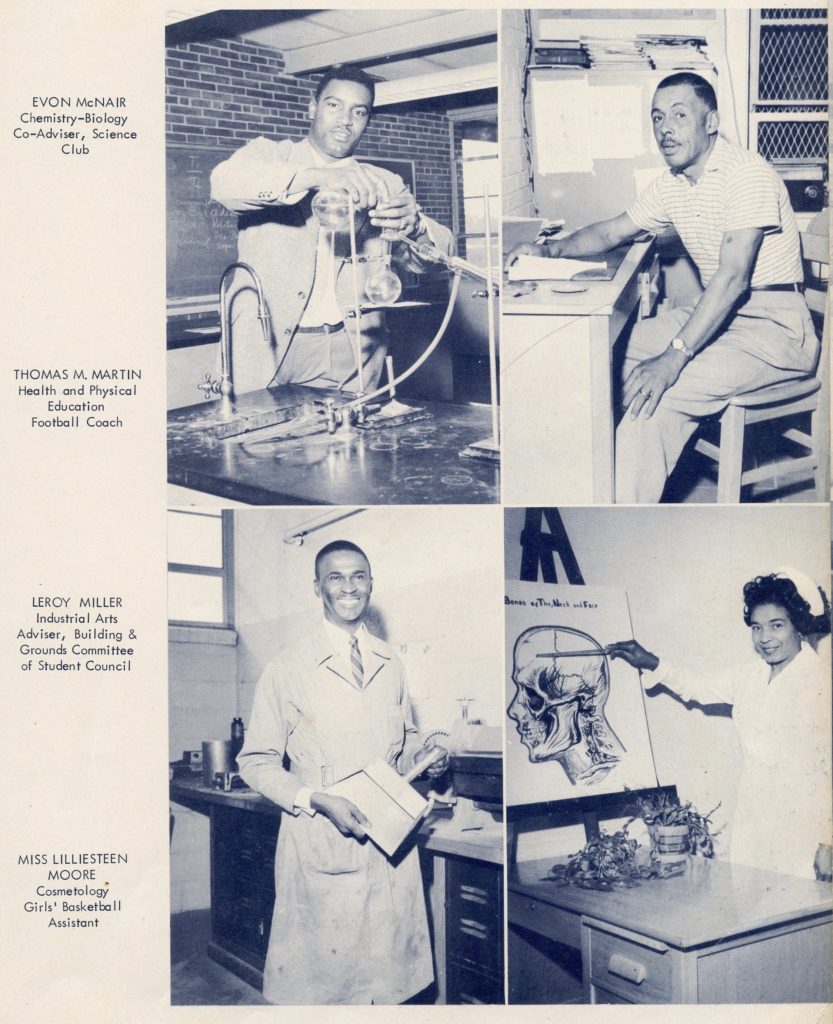

Many West Charlotte teachers brought experience with wider worlds. Math teacher and athletic coach Jack Martin had attended Johnson C. Smith for both high school and college, because his hometown of Chester, South Carolina had no high school for blacks. After captaining the Johnson C. Smith football team, he had headed to New York University for a masters in physical education before returning to Charlotte to teach. Industrial arts teacher Pop Miller, who grew up in Salisbury, had been drafted by the Army days after he graduated from North Carolina A & T, and served as part of the “Red Ball Express” that supplied American troops as they fought their way across France and into Germany. He brought home a wealth of mechanical and logistical knowledge, as well as four Bronze Stars. Durham native Johnny Holloway, who became West Charlotte’s music director in 1950, had done his wartime service in the 337th Army Band, pursued graduate work in music at Ohio State, and spent summers in New York City playing his tenor saxophone with the nation’s jazz greats.

These teachers had a demanding job. Preparing young people for a world that would be both competitive and discriminatory required a multifaceted approach, one that started with teaching students to think for themselves. The North Carolina Teachers Record, the journal of North Carolina’s black teachers’ organization, stated the case bluntly in 1936: “The successful teacher is not the one who feeds his pupils on facts, but the one who inspires them to test every fact, however ancient or moss-covered it may be. There is no evidence that North Carolina is in need of an additional supply of rubber stamps.” The endeavor also involved building students’ confidence. “We were really taught.” recalled Sarah Moore Coleman, who went on to a long career in social service, school administration and political organizing. “They taught us to have so much dignity and self-assurance. And not to be afraid.”

Nurturing this kind of independent fortitude required a multiplicity of efforts. Teachers tolerated little nonsense. Saundra Davis’s favorite teacher was Lilliesteen Moore, the poised cosmetology teacher who had strict standards for both learning and ladylike behavior. Davis laughed as she recalled the year that two members of the football team signed up for cosmetology. “You know most people think when you say cosmetology, they think you come in and just learn to do hair a little,” she said. “But you’ve got to learn everything about the body. You’ve got to know what to do for burns and everything else. She just stayed on them all the time. They thought it was a play thing, but she made them learn.”

Staff members also sponsored a wide range of activities that fed body and soul as well as mind. Sarah Coleman particularly loved the ballroom dancing classes taught by English teacher Samuel Moore. “We used to dance to music like the Viennese Waltz,” she recalled. “And they used to swing us up in the air. It was just so beautiful. I never will forget it.” Pop Miller was renowned for his devotion to school rules, enforced by liberal use of his ever-present wooden paddle. But he also believed that high school should be a joyful time.” My high school days were the happiest days of my life,” he explained. “I didn’t have a care in the world. And I always wanted the same thing for all of the students. That’s the time when you start looking at girls. You start dancing and doing the things that you enjoy out of life. And I think you prepare for life, and I think every youngster should have that experience.”