April 20, 1971

April 20, 2021

Two historic days, 50 years apart.

In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg that communities had a Constitutional duty to desegregate their public schools, even if it required busing students across town.

In 2021 a jury in Minneapolis convicted former police officer Derek Chauvin of murdering George Floyd.

In the weeks since the anniversary and the conviction, news has come at disorienting speed: MaKhia Bryant, Anthony Alvarez, Andrew Brown, Jr., Mario Gonzalez, on and on and on.

Amid this whirl of events, I want to take a moment to reflect on Swann and Chauvin, and the way they speak to the role of law in the long American struggle for freedom and justice. Laws, rulings, acquittals, and convictions provide powerful tools and symbols. They do not produce change on their own. That work requires courageous individuals and communities.

In the mid-twentieth century, challenging school segregation required Black families to place their names on lawsuits and suffer the consequences. In Clarendon County, South Carolina, for example, the courageous plaintiffs in Briggs v. Elliot lost jobs, were denied loans, were attacked in their homes at night and charged with crimes when they fought back. Several were forced to leave the community; some never recovered from their losses.

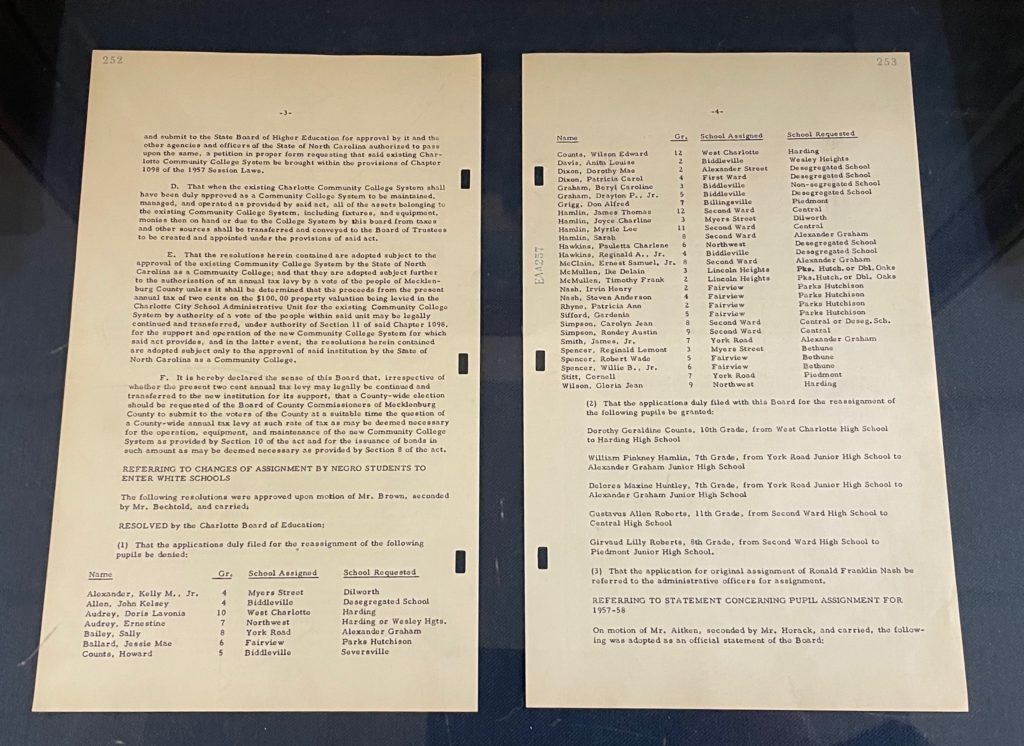

When the Supreme Court ruled in Brown that segregated schools must be eliminated, southern school boards forced African American families to put themselves on the line once again. Many states, including North Carolina, enacted “freedom of choice” plans that required Black families to request transfers to historically white schools, and thus expose themselves to intimidation and harassment.

In 1957, Black families in Charlotte requested transfers for 40 students. The Charlotte school board approved five: Dorothy Counts, William Hamlin, Delores Huntley, Gus and Girvaud Roberts.

Over that summer, William Hamlin’s family received so many threats that Hamlin’s father sent the children to stay with relatives in Virginia, then moved across town. That fall, he enrolled William in a historically Black school.

In September, when Dorothy Counts arrived at Harding High, she was met with an angry white mob, which neither law enforcement nor school administrators did much to contain. Photographs of her ordeal circulated around the world. After several days of nonstop harassment, she withdrew.

Black Charlotte families continued to request transfers and the school board continued to deny them. In the fall of 1964, a full decade after Brown, only 722 of Charlotte’s 20,000 Black students attended predominantly white schools.

In January of 1965, attorney Julius Chambers filed the Swann case to press for greater change. A few months later, bombs exploded at the homes of Chambers and two of the activist families who had signed on to the case.

The plaintiffs persisted. In 1969, Chambers convinced federal judge James McMillan to order the full desegregation of Charlotte Mecklenburg schools, a decision that required an unprecedented level of cross-town busing. In 1971, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld McMillan’s decision.

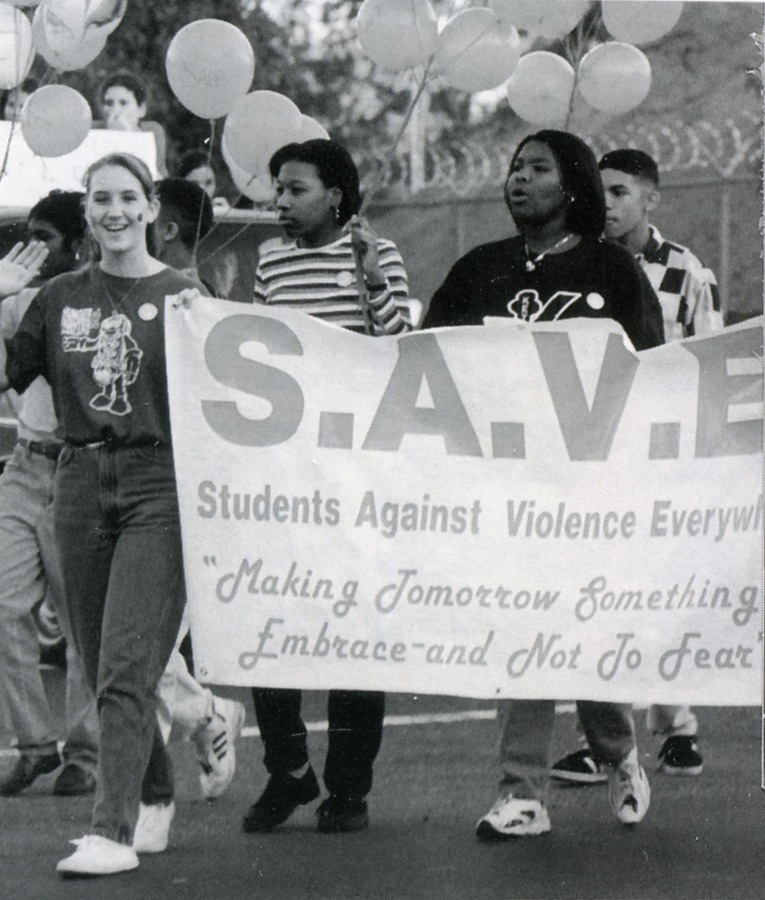

Even then, however, the outcome depended on Charlotte residents themselves. Not until three years after the Supreme Court decision, when a diverse group of residents crafted a busing plan that included the entire community, did the situation stabilize. Then, thanks to years of dedicated efforts on the part of students, parents, staff and community, Charlotte Mecklenburg became the most desegregated major school system in the nation for nearly a quarter century. The achievement boosted Charlotte’s image as a progressive southern city and sparked enormous civic pride.

But, 50 years on, the long-term fate of Swann also serves as a warning. As Charlotte grew, and as national politics took a conservative turn, the city developed in ways that widened physical divides between older, predominantly African American city neighborhoods and new, predominantly white suburbs built farther and farther from the center of town. Support for desegregation ebbed, and as the twenty-first century began, a new lawsuit forced the school system to dismantle its busing program. Housing patterns, along with an anxious scramble by parents of means to enroll their children in low-poverty, high-performing schools, led to rapid resegregation. Today, Charlotte Mecklenburg is one of the most segregated school systems in North Carolina.

Some of these themes are already emerging in the Chauvin case. Most notably, it took action from people on the ground – especially the recording made by 18-year-old Darnella Frazier – to reveal the truth about George Floyd’s murder, and to pressure authorities to pursue a prosecution.

The conviction that emerged from those courageous efforts provides a measure of justice, and an important symbol. But as the deaths of MaKhia Bryant, Andrew Brown, Jr. and so many others have made clear, it will take ongoing efforts in multiple arenas to turn that symbol into reality. We all need to roll up our sleeves.