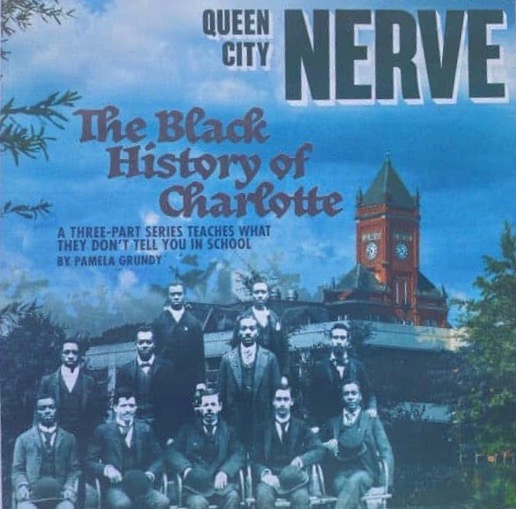

Shout out to the Queen City Nerve for making space for history. This Wednesday (July 29) they published the first installment of a series I’m writing about African Americans in Charlotte history.

That first part covers the remarkable lives that African Americans shaped in post-Civil War Charlotte, and the way the White Supremacy Campaign of 1898 obliterated much of that progress.

Future installments will detail the communities that Black Charlotteans created during segregation, the civil rights movement, urban renewal, school desegregation/resegregation and some of the post-civil rights developments that have shaped the challenges we in Charlotte face today.

As well as charting the long history of Black striving, in both good times and bad, I try to show how barriers and opportunities have shifted over time. I hope that learning about the ways that activists of different eras wrestled with the specific challenges they faced will be of use to present-day efforts to make Charlotte a better, fairer place.

For that reason, this is also a story about the powerful white business leaders that have run the city since before the Civil War. Championing a vision of progress, prosperity and order, these leaders have worked tirelessly to build Charlotte into a larger, wealthier, more respected city – all while keeping the “better class” of residents in charge.

In general, this strategy has involved a moderate approach to race. When racial advancement was seen to help the city as a whole – when it gave African American workers reasons to come to or stay in Charlotte, when it kept the federal government out of city affairs, when it boosted the city’s national image – white leaders encouraged some degree of change.

But when African Americans stood in the way of “progress” – when they challenged the hold of business interests over the state legislature, when they lived on prime center-city land that civic leaders wanted to use for more “productive” purposes – those leaders swept them aside.

This multifaceted story raises the challenge that anyone who writes about Black history has to face: how to balance the hard work and achievements of Black men and women with the oppression they have confronted throughout this nation’s history.

Focusing on achievement can obscure historical wrongs. Focusing on oppression can turn people into faceless victims. It’s essential to understand both. I try to walk that line – sometimes more successfully than others.

My History

I write this as a white cis woman born just over 58 years ago in Houston, Texas. I came to African American history in graduate school. It was an exciting time – the late 1980s – and an exciting place – U.N.C. Chapel Hill. Black history was coming into its own, with new subjects, new sources, new interpretations. There was so much to learn.

I was also surrounded by remarkable scholars, including a fellow Ph.D. candidate named Tom Hanchett. Most of us were white. Academia is a privileged arena, and while Black scholars are growing in numbers and influence, they’re aren’t nearly enough of them. So the rest of us do what we can. You’ll find many of my friends’ books, often published by U.N.C. Press, in the reading suggestions below.

It is, of course, a challenge to write about a history you haven’t lived through. During nearly 30 years of working as a writer, teacher and museum curator here in Charlotte, I’ve done my best to listen.

This journey started with the generosity of Vermelle Ely and her colleagues at the Second Ward High School National Alumni Foundation, and with Rudy Torrence and many other members of the West Charlotte High School National Alumni Association. I try to do right by the stories they and so many others have entrusted to me. Any failings are my own.

I got the idea for this series back in June, when Betsy Mack from the Charlotte Hornets asked me to help bring head coach James Borrego up to speed on Charlotte’s racial history.

Those conversations led me to realize that while many people want to know this history, its pieces are scattered across books, articles, websites, livestreams and countless other places. It’s hard to find an overview that puts them in a clear chronology and brings them into conversation with each other.

Many of us are trying to figure out what roles we can play in the ongoing efforts to remake this upended world where we now live. Maybe, I thought, putting these stories together could be one of mine.

Reading for Race in Charlotte/North Carolina History

(in roughly chronological order)

Janette Thomas Greenwood, Bittersweet Legacy: The Black and White “Better Classes” in Charlotte, 1850-1910 (University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

Thomas Hanchett, Sorting out the New South City: Race, Class, and Urban Development in Charlotte, 1875-1975 (University of North Carolina Press, 1998, new edition 2020).

Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore, Gender & Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920 (University of North Carolina Press, 1996, new edition 2019).

David Zucchino, Wilmington’s Lie: The Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy (Atlantic Monthly Press, 2020).

Fannie Flono, Thriving in the Shadows: The Black Experience in Charlotte and Mecklenburg County (Novello Festival Press, 2007).

Jill Snider, Lucean Arthur Headen: The Making of a Black Inventor and Entrepreneur (University of North Carolina Press, 2020).

Karen L. Cox, Dixie’s Daughters: The United Daughters of the Confederacy and the Preservation of Confederate Culture (University of Florida Press 2003, new edition 2019).

Rose Leary Love, Plum Thickets and Field Daisies: A Memoir (Novello Festival Press, 1996).

Vann R. Newkirk, “The Development of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in Metropolitan Charlotte, North Carolina 1919-1965 (Ph.D. diss., Howard University, 2002).

Willie James Griffin: “Courier of Crisis, Messenger of Hope: Trezzvant W. Anderson and the Black Freedom Struggle for Economic Justice” (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 2016).

Sarah Thuesen, Greater than Equal: African American Struggles for Schools and Citizenship in North Carolina, 1919-1965 (University of North Carolina Press, 2013).

Pamela Grundy, Color and Character: West Charlotte High and the American Struggle over Educational Equality (University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

William H. Chafe, Civilities and Civil Rights: Greensboro, North Carolina, and the Black Struggle for Freedom (Oxford University Press, 1980, 1981).

Richard Rosen and Joseph Mosnier, Julius Chambers: A Life in the Legal Struggle for Civil Rights (University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

Davison Douglas: Reading, Writing and Race: The Desegregation of the Charlotte Schools (University of North Carolina Press, 1995).

Frye Gaillard, The Dream Long Deferred: The Landmark Struggle for Desegregation in Charlotte, North Carolina (University of South Carolina Press, 3d edition, 2006).

Matthew D. Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. (Princeton University Press, 2006).

Pam Kelley, Money Rock: A Family’s Story of Cocaine, Race, and Ambition in the New South, (The New Press, 2018).

Roslyn Mickelson, Stephen Smith and Amy Hawn Nelson, eds. Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow: School Desegregation and Resegregation in Charlotte. (Harvard Education Press, 2015).

Greg Jarrell, A Riff of Love: Notes on Community and Belonging (Cascade Books, 2018).