Thanks again to Queen City Nerve for making space for history – the second installment of my five-part series on Black Charlotte history.

This piece started with the kind of research that historians love best. Some years ago, when I was studying West Charlotte High, I read First Class by Alison Stewart, a terrific history of D.C.’s renowned Dunbar High.

The book included an intriguing snippet about Samuel Pride, who was Stewart’s great-grandfather: “Professor Pride was also known to stay up all night on the family porch because some local KKK members let it be known that they did not appreciate the fact that he and some like-minded individuals helped establish a high school for colored children in Charlotte.”

I mentioned the incident in a footnote in Color & Character, and left it at that (when historians find something interesting that we don’t have time to pursue, we’ll often drop it in a footnote, like a bread crumb, and hope some other researcher will pick up the trail). But when I started this series, I wanted to know more.

I reached out to Stewart, who’s now a radio show host in New York, and learned a good bit more about the family. Stewart had heard the story of Pride guarding the family home from her grandmother, who was about 10 years old when the threats started coming.

Then, with the help from good friend and researcher extraordinaire Jill Snider (whose recently published book on North Carolina Black inventor Lucean Headen should be required reading for anyone interested in African American history) I started to put some more pieces together.

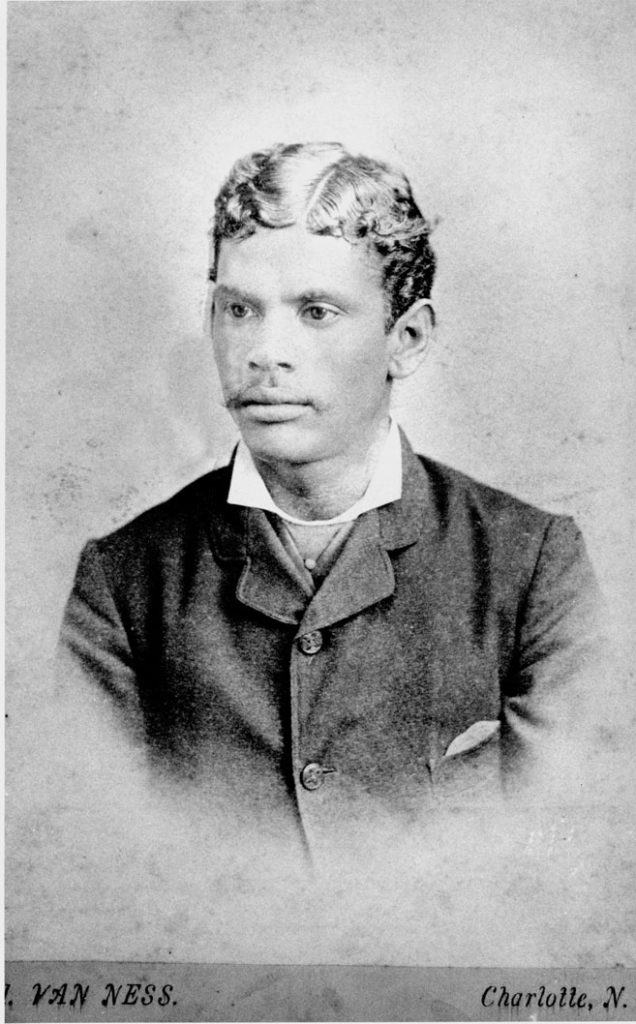

As soon as I started digging, it became clear that Samuel Pride was one of those remarkable Black Charlotteans whose accomplishments are far less well-known than they should be. Born in slavery in South Carolina, he came to Charlotte after the Civil War and quickly made his mark.

Once I started looking for Pride, it seemed that he was everywhere: teaching mathematics at Biddle University, heading up a regional Presbyterian Sunday School organization, participating in heated debates at meetings of Charlotte’s Republican Party. At the time of the threats, he was principal of the Myers Street School, Charlotte’s first public school for African Americans.

Rose Leary Love mentioned Pride in her lovely Brooklyn memoir Plum Thickets & Field Daisies: “He is the principal I remember best, and when I think of Mr. Pride, I have vivid impressions of his straight, shiny black hair that seemed to gleam like patent leather to me.”

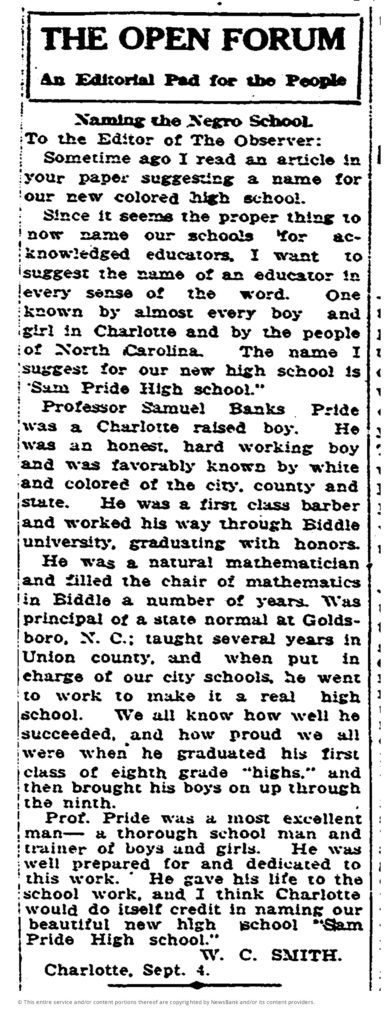

The best find, though, was a letter in the Charlotte Observer in the fall of 1923, just as Second Ward High School was getting ready to open. Samuel Pride did not live to see his dream realized – he passed away in 1917 from a lung ailment. But his friends did not forget him or his efforts.

Shelia Bumgarner of the Charlotte Mecklenburg Library also sent me a copy of the remarkable picture published at the top. It’s a recent library acquisition – it was found in someone’s trash! – and it shows the board of the Charlotte-based Afro-American Mutual Insurance Company.

As Tom Hanchett notes in his recently reissued Sorting Out the New South City, in the 1910s the company advertised itself with the promise that “an Afro-American policy, by an Afro-American agent, made by Afro-American clerks, on an Afro-American husband, an Afro-American wife, or an Afro-American child, makes an Afro-American home independent in the hours of sickness or death.”

In the picture, barber and businessman Thad Tate is standing – looking so very elegant. At center, staring straight into the camera, is Henry Houston, who founded the Charlotte Post. I’m pretty sure the man at the far left, pen in hand, is Samuel Pride.

There is so much left to learn.